Updated 7 August 2023 (c) 2023

Introduction

The “big bang” is a name given to the origin event of our universe, which scientists now date at roughly 13.8 billion years ago, according to the latest data released by the Planck project [Cho2013]. The term was actually coined by physicist Fred Hoyle during a radio broadcast in 1949. He favored the alternative “steady state” theory, and he used the term “big bang” as a derisive nickname for the theory that is now widely accepted for the evolution of the universe.

The big bang cosmology originally grew out of Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which was published in 1915. In 1922, Alexander Friedmann, a Russian mathematician, derived equations from general relativity showing that the universe might be expanding, in contrast to the static universe that Einstein had assumed. Einstein originally posited a nonzero value for the cosmological constant, a term in his equations, but after the expansion of the universe was discovered, he lamented that this was his greatest blunder and set the constant to zero [Davies2007, pg. 58]. In 1924, American astronomer Edwin Hubble measured the distance nearby spiral nebulae and showed that these systems were actually other galaxies, not merely objects within the Milky Way. In 1927, Georges Lemaitre, a Belgian Roman Catholic priest, suggested that the recession of these nebulae was due to the expansion of the fabric of universe. In 1929, Hubble confirmed this hypothesis, by showing that the distances to these galaxies were roughly proportional to their outward velocities, as measured by the degree to which their light spectra was shifted to the red (this fact is now known as Hubble’s Law). This inferred that the entire universe is expanding, not only away from us but also away from every other position in space — much like dots on the surface of an expanding balloon all appear to be moving away from each other. In that case, there must have been a time when the universe was very much more dense than it is today.

Experimental confirmations

The big bang cosmology theory received substantial confirmation from an important discovery in 1964. Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, two radio astronomers in New Jersey, used a large horn antenna, which had been developed at Bell Laboratories for satellite communication, to make some measurements of radio waves. After being frustrated by some noise in their antenna that they were unable to eliminate, they finally realized that this noise was astronomical in origin. What’s more, since it was isotropic (i.e., constant in all directions), not more intense in the direction of the sun or Milky Way, it must be coming from the cosmos itself. A group of physicists at nearby Princeton University, led by Robert Dicke, immediately recognized the significance of the noise — it was the primordial echo of the universe itself from 300,000 years after the big bang. Indeed, the noise spectrum appeared to fit a “black body” radiation curve that had been predicted earlier by other researchers from theoretical grounds alone [Silk1989, pg. 82-85].

At about the same time, theoretical calculations by several researchers concluded that the big bang cosmology would have produced a universe that is roughly 75% hydrogen, 25% helium, with traces of He-3 and Li-7 (heavier elements are produced by a different process in the explosion of stars). Careful measurements verified these abundance figures in impressive detail [Guth1997, pg. 101-103].

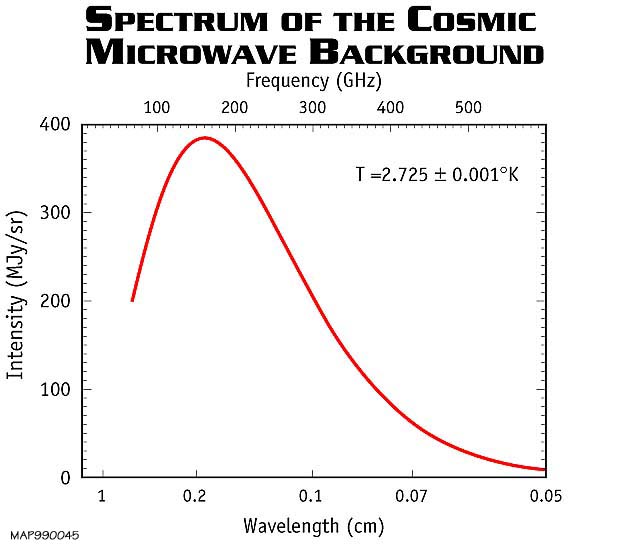

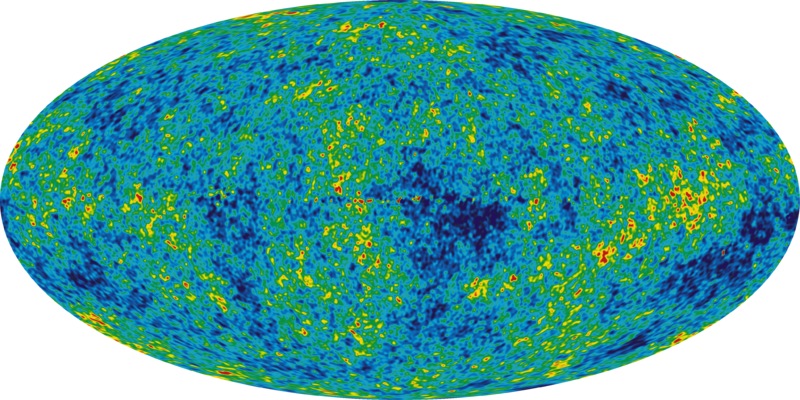

More recent astronomical measurements continue to confirm the big bang model. For example, in 1993, measurements of the cosmic microwave background using the Cosmic Microwave Background Explorer (COBE) satellite were found to perfectly fit a black body radiation curve with a characteristic temperature of 2.725 K, plus or minus 0.01 K. Data obtained from the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) spacecraft, which was in operation from 2001 through 2010, showed even more spectacular agreement — plus or minus 0.001 K. See the plot below (top). In this graph, the vertical error bars of the data, if shown, would be much too small to be distinguished from the curve itself! It should also be noted that careful measurements of the microwave background measurement show that this radiation is isotropic (equal in all spatial directions) to within one part in 100,000. Interestingly, though, if it were perfectly isotropic, this would be in conflict with theory requiring small early fluctuations in matter density to provide seeds for the subsequent formation of stars and galaxies. Fortunately, though, in the early 1990s fluctuations were found, at just the level predicted by theory [Tegmark2014, Ch. 5].

Below (bottom) is a map of these fluctuations, again based on WMAP data (both photos courtesy NASA):

The most recent data has been obtained by the Planck orbiting observatory, which began operation in 2010. Like the WMAP mission, the Planck satellite permits scientists to analyze the “angular power spectrum” of the data (the degree of correlation between the data in one direction with the data in different directions across the sky), but with even greater accuracy and resolution than WMAP. In March 2013, the Planck project released its latest results. Researchers concluded that the universe consists of 4.9% ordinary matter, 26.8% “dark matter” (which exhibits itself only through gravitational effects), and 68.3% “dark energy” (which is believed to be responsible for the accelerating expansion of the universe). This data also permitted the Planck team to pin down the age of the universe at 13.8 billion years, slightly older than the 13.75 billion year age estimated by WMAP [Cho2013].

A very interesting online tool, constructed by the WMAP team, permits one to “design” a universe by varying the composition of matter (atoms, cold dark matter and dark energy) together with the Hubble constant (which is related to the age), to obtain the best fit to the angular spectrum data [WMAP2009].

In March 2010, the age of the universe was accurately measured by a completely different approach. A team of researchers from several U.S. and European institutions employed a technique known as gravitational lensing (a phenomenon related to general relativity) to measure the distances traveled by light rays from a distant galaxy to the earth along different paths. By calculating the time it took to travel along each path and the effective speeds involved, these researchers were able to infer how far away the galaxy lies and also the overall scale of the universe, plus some details of its expansion. The researchers confirmed that the age of the universe is 13.75 billion years old, plus or minus 0.17 billion years, in agreement with the age found by the WMAP and, more recently, by the Planck team [SD2010i].

These results are further confirmed by measurements of the universe’s expansion and acceleration, based on the observation of Type Ia supernovas. These results are now accurate enough to rule out one alternative theory to the accelerating universe, namely that the Milky way lies in a large void [SD2011f].

Chronology of the big bang cosmology

Here is a brief (and abbreviated) sketch of the big bang chronology, according to the best current theories:

- Planck epoch. During the first 10-43 seconds, all fundamental forces (electromagnetism, weak nuclear force, strong nuclear force and gravitation) are indistinguishable in strength.

- Grand unification epoch. During the first 10-36 seconds, as the universe expands and cools from the Planck epoch, gravitation begins to separate from electromagnetism and the strong and weak nuclear forces. The temperature was roughly 1027 K.

- Electroweak (inflation) epoch. Immediately after the grand unification epoch, the universe underwent an explosive inflationary stage, where the fabric of the universe grew by approximately 30 orders of magnitude. After this inflation stopped, matter consisted of a quark-gluon plasma. Soon the universe cooled to permit a very small excess of quarks over antiquarks, which resulted in the predominance of matter over antimatter in the present universe. This phase lasted until 10-12 seconds.

- Quark epoch. The universe continued to grow in size and fall sharply in temperature, permitting the four fundamental forces and elementary particles to appear in their present form. This lasted until 10-6 seconds.

- Hadron epoch. During this period, quarks and gluons combined to form particles such as protons and neutrons. This lasted until 1 second.

- Photon epoch. During this period, the universe was dominated by photons. After the first three minutes, when the temperature had fallen to “only” one billion degrees K, some neutrons and protons combined in a process of nucleosynthesis to produce deuterium and helium and trace amounts of lithium and beryllium (although most protons remained as hydrogen nuclei). This lasted until 379,000 years had elapsed.

- The dark age. After about 379,000 years, electrons combined with protons and helium nuclei to form atoms. At this point radiation was able to pass through space mostly unimpeded. The relic of that “first light” radiation today is the cosmic microwave background.

- Formation of stars and galaxies. Over the next 100 million years so, subtle inhomogeneities in the original distribution of matter after the big bang, acting under gravitational attraction, formed the first stars. These subsequently coalesced into galaxies.

- Formation of the heavy elements. Several billion years later, as the first generation of stars began to exhaust their nuclear fuel and die, the resulting stellar explosions produced carbon atoms and all heavier elements observed around us today (and which constitute much of the mass of our own bodies).

The inflation controversy

In spite of all of these results spanning the past 50 years or more, controversies remain. One of these is lingering dissatisfaction with the inflation scenario in the first inconceivably brief instant after the big bang, in which, according to theory, the fabric of the universe expanded by some 30 orders of orders of magnitude.

While inflation made sense according to the original mathematical formulation of the inflation process developed back in the 1970s and 1980s, it seems significantly less satisfactory today, and even some leading figures in the field now believe that this scenario needs to be rethought. More modern mathematical formulations have many “ad hoc” parameters and assumptions, many of which are increasingly dubious, or which, as with considerations of the “multiverse,” must invoke the anthropic principle to explain the early evolution our universe. For example, highly improbable conditions are required for the inflation process to be initiated. Worse, it appears that the most natural course of events is for the inflation process to continue indefinitely, producing an infinite variety of outcomes, so that it is difficult to make any firm observational predictions from the theory.

These difficulties had led even long-time supporters of inflation to question the theory’s viability (although not the viability of the overall big bang cosmology). Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University is one vocal detractor. In 2012 he declared, “We thought that inflation predicted a smooth, flat universe. Instead, it predicts every possibility an infinite number of times. We’re back to square one.” Similarly, Sean Carroll, a cosmologist at the California Institute of Technology, explains, “Inflation is still the dominant paradigm, but we’ve become a lot less convinced that it’s obviously true. … If you pick a universe out of a hat, it’s not going to be one that starts with inflation.” [Gefter2012].

These controversies were re-ignited with the March 2014 discovery of gravitational wave ripples in the cosmic microwave background radiation, which were heralded as the first solid experimental confirmation of the inflationary theory of the big bang [Overbye2014a]. Proponents of the multiverse were quick to point out the implications. As Alan Guth, the MIT physicist who founded inflation theory, explains, “Most inflationary models, almost all, predict that inflation should become eternal.” Frank Wilczek adds, “There doesn’t seem to be anything unique about the event we call the big bang. It is a reproducible event that could and would happen again, and again, and again.” [Moskowitz2014].

But critics of inflation and the multiverse were also quick to sow skepticism. As Peter Coles of the University of Sussex, UK, writes, “Perhaps there is a part of the multiverse in which the BICEP2 results for inflation provide evidence for a multiverse, but I don’t think we live there.” [Moskowitz2014]. What’s more, the BICEP2 experimental evidence itself, on which the March 2014 discovery was based, has been called into question. A team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley argues that the “twisting” effect cited in the gravitational wave study could just as easily be accounted for as a result of dust in the Milky Way [Cowen2014]. The latest data points even more strongly to dust as an explanation, so the current consensus is that the BICEP2 data can say nothing about inflation one way or the other [Wolchover2015].

In the latest development, researchers are starting to take a hard look at the entire inflation scenario. One worrisome development is that attempts to provide a proper theoretical underpinning of inflation have produced, if anything, an embarrassment of riches — there are literally hundreds of different theoretical formulations of inflation, each generating different rates of of inflation, different degrees of stretching of the space-time fabric, different degrees of quantum-mechanical variation leading to different degrees of variation in the present-day cosmic microwave background radiation. As Anna Ijjas, Paul Steinhardt and Abraham Loeb wrote in a 2017 Scientific American article, “Inflation is such a flexible idea that any outcome is possible.” [Ijjas2017].

So we may well see, in the next few years, some fundamental rethinking of inflation. One alternate idea is a “big bounce” scenario, wherein a precursor universe shrank to a small volume and then expanded to we see today. It will be interesting to see how these controversies play out. See Inflation for additional details.

Conclusions

In short, the results of recent satellite measurements and large-scale particle physics experiments have enabled scientists to confidently extrapolate the history of our universe back to an inconceivably early epoch after the big bang, and have been able to date the big bang as an event approximately 13.8 billion years ago. Certainly there are significant puzzles remaining in the theory, not the least of which are questions about the inflation process, as mentioned above. But even some of the alternate theories to inflation, such as the “big bounce” scenario, still involve a universe that arose approximately 13.8 billion years ago, and then expanded and elaborated into today’s universe: all available data requires this conclusion.

In other words, the overall outline of the big-bang evolution of the universe, as summarized above, is on very solid ground, both theoretically and empirically. In this regard, the status of big bang cosmology is analogous to that of the theory of biological evolution on earth — while there are many questions as to how the process started and what processes and laws governed very early epochs of the process, the overall history since the origin is hardly in doubt.